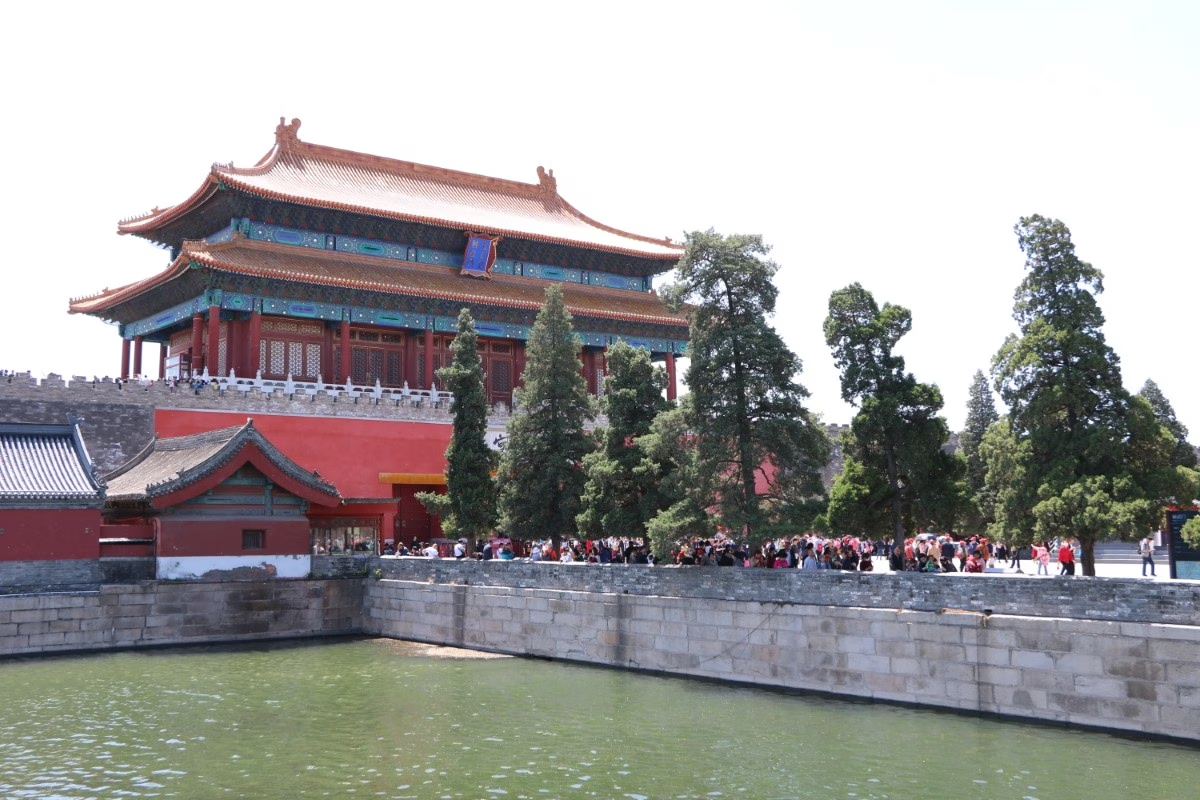

The Forbidden City – known as Gùgōng (故宫) in Chinese – is a living relic of China’s imperial past and a must-see centerpiece of any Beijing trip. Enclosed by towering red walls and a wide moat at the city’s heart, this sprawling palace complex, once hidden from the public, now welcomes millions of visitors yearly. With its golden rooftops, grand halls, and 600 years of history, the Forbidden City offers an unforgettable journey back in time. This guide will equip you with everything you need – from a bit of imperial history to practical tips – for a casual yet gratifying visit to this UNESCO World Heritage Site.

A Glimpse into the Forbidden City’s History

The Forbidden City was commissioned in 1406 by the Ming Dynasty’s Emperor Yongle and constructed over 14 years (1406–1420). For the next 500 years, it served as the ceremonial and political center of China, home to 24 emperors from the Ming and Qing dynasties. Commoners were strictly forbidden to enter its 720,000 square meters of walled palaces – hence the name “Forbidden City.” After the last emperor, Puyi, abdicated and left the palace in 1924, this vast imperial compound was transformed into the Palace Museum in 1925, finally opening its doors to the public. In 1987, it was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site for its immense cultural significance.

Despite turmoil in the 20th century, including war and revolution, the Forbidden City remains remarkably preserved as the world’s largest ancient wooden palace complex. Ongoing restoration (notably for the palace’s 600th anniversary in 2020) means many buildings shine as they did in imperial times. Walking through the Meridian Gate today, you’ll be tracing the footsteps of emperors, empresses, and courtiers, experiencing firsthand the grandeur and mystery of China’s last imperial palace.

Visitor Information at a Glance

To help plan your visit, here’s a quick-reference table of key information:

| Key Info | Details |

|---|---|

| Ticket Prices (Apr–Oct) | ¥60 for adults (Apr–Oct); ¥40 Nov–Mar. Children (under 6 or <1.2m): Free; Youth 7–18: ¥20; Seniors (60+): half-price. |

| Additional Exhibitions | ¥10 each for Treasures Gallery and Clocks Gallery (optional exhibits inside). |

| Daily Visitor Cap | 40,000 visitors (may increase ~25% to ~50,000 during peak holidays) – reserve tickets early. |

| Opening Hours | Apr–Oct: 8:30–17:00 (last entry 16:00); Nov–Mar: 8:30–16:30 (last entry 15:30). |

| Closed Days | Mondays (except on national public holidays). |

| Entry Gate | South entrance at Meridian Gate (午门 Wǔmén) – the only public entry point. |

| Exit Gates | North exit at Gate of Divine Prowess (神武门 Shénwǔmén) (most common) or East exit at East Prosperity Gate (东华门 Dōnghuámén). |

| Recommended Visit Time | 2–4 hours for main highlights; up to a full day if exploring extensive side halls and museums. |

| Best Times to Visit | Weekdays (Tue–Fri) are quieter; arrive early morning (around opening) or after 14:00 to avoid peak crowds. Avoid Chinese public holidays (e.g. first week of May/Oct, Chinese New Year) due to extremely high crowds. |

| Official Booking | Online up to 7 days in advance; real-name reservation with passport required. No on-site ticket sales for general visitors (see tips for exceptions). |

| (All prices in Chinese Yuan/RMB. Information current as of 2025.) |

Tickets and Entry Reservations

All visitors must purchase tickets in advance – the Forbidden City does not sell walk-in tickets at the gate for general admission. Tickets are released on the official Palace Museum website (with an English version available) and via the Palace Museum’s WeChat mini-program (Chinese only). Sales open 7 days ahead at 8 PM daily, and tickets often sell out quickly during holidays and weekends, so plan to book as early as possible. Each visitor is limited to one ticket per day, and you’ll need to input your passport details when booking – your passport then acts as your “ticket” for entry (you’ll simply scan it at the gate, no paper ticket required).

- Daily Capacity: Note that the Palace Museum caps visitation at 40,000 people per day to protect the site. In peak periods like the May 1st and October National Day holidays or summer vacation, they may raise capacity by about 25% (up to ~50,000), but tickets still vanish fast. Always secure your tickets in advance, or enlist a hotel/travel agent to help if you encounter difficulties with the Chinese booking systems.

- Passport Requirement: Your passport is mandatory for booking and entry. Bring the same passport used for the reservation on the day of your visit – security will check it at the entrance. (If you’re a domestic traveler, a Chinese national ID or equivalent is used instead.)

- Sold Out? If you find tickets completely sold out online, don’t despair. There is a special workaround for foreign visitors: a new policy allows foreign travelers to purchase same-day tickets in person at the Forbidden City’s ticket office even when online tickets are sold out. To use this loophole, do not go to the main Meridian Gate entrance (they won’t let you in without an online reservation). Instead, enter from the side at Donghuamen (East Prosperity Gate) where the ticket office is located. Bring your passport and some cash, and you can buy a ticket on the spot. (If you’re approaching from the Tiananmen Square side, note you’ll need a free Tiananmen Square entry reservation made a day before accessing the square and then reaching the ticket office from inside the square.) This policy is a lifesaver for last-minute planners, but use it as a backup – booking online in advance is still highly recommended to ensure a smooth visit.

Ticket prices for adults are ¥60 in the April–October high season and ¥40 in the November–March low season. Children 6 or under (or under 1.2 m height) enter free, and ages 7–18 enjoy discounted ¥20 entry. Seniors over 60 also get 50% off. Two special exhibition areas inside – the Treasure Gallery (in the Palace of Tranquil Longevity) and the Clocks & Watches Gallery (Hall of Ancestry Worship) – require separate ¥10 tickets (half-price for students and seniors). If you’re interested in seeing the imperial jewels, ceremonial artifacts, or an amazing collection of antique timepieces, it’s worth the extra few yuan for these exhibits. (Tip: You can purchase the add-on exhibition tickets along with your main ticket online, or buy them at a kiosk inside the palace near those exhibit entrances.)

Opening Hours and Best Times to Visit

The Forbidden City’s hours vary by season, and the last entry is one hour before closing. During April–October, the museum opens at 8:30 AM and stops entry at 4:00 PM, with all visitors cleared out by 5:00 PM. In the winter months (November–March), it still opens at 8:30 AM, but last entry is earlier, at 3:30 PM, with closing at 4:30 PM. Plan accordingly so you’re not rushed – for instance, if you arrive at 3 PM in winter, you’ll only have 1.5 hours to explore.

Closed on Mondays: The Palace Museum is generally closed every Monday to allow maintenance and rest (the only exceptions are Mondays that fall on national holidays, when it stays open). So, avoid Monday in your itinerary (and note that if you book online, the system won’t even offer Mondays unless it’s a holiday period).

Best days and times: To enjoy the Forbidden City with lighter crowds, aim for a weekday visit – Tuesday through Thursday tend to be the least crowded. Wednesdays or Thursdays outside of holidays are often ideal. Weekends see heavier domestic tourism, and Chinese public holidays (especially the first week of May and October, and the Lunar New Year period) bring massive crowds – it’s best to avoid those peak holiday weeks entirely if you can.

For timing in the day, arrive early or late. If you can get to the Meridian Gate right at opening (8:30 AM), you’ll beat the tour groups to some of the major halls and enjoy a cooler, quieter morning. The first hour of opening is comparatively peaceful, and you can always linger later. Alternatively, entering in mid-afternoon (after 2 PM) can also be relatively calmer once many big groups have left. In summer, a late afternoon visit also spares you the worst midday heat. Keep in mind that no matter when you go, the Forbidden City is the most visited museum in the world, and certain iconic spots will always have a crowd, but these timing strategies can significantly improve your experience.

Seasonal considerations: Beijing’s weather is extreme – hot summers, cold winters – but the Forbidden City holds its charm year-round. Arguably, the best seasons are spring (April–May) and autumn (Sept–Oct), when temperatures are mild and the palace courtyards are especially beautiful (peach blossoms in spring, golden leaves in fall). Crowds during these shoulder seasons are moderate. Winter (Nov–Feb) is the quietest time – if you don’t mind the cold, you’ll find far fewer visitors and an almost magical atmosphere, especially if it snows (the sight of the palace dusted in snow is worth the shivers!). Just bundle up well. Summer (June–Aug) is the busiest and can be tough with Beijing’s sweltering heat and occasional downpours. There is very little shade in the Forbidden City’s open courtyards, so if a summer visit is your only option, wear a hat, use sunscreen, and carry water. Whenever you visit, try to avoid the “Golden Week” national holidays (first week of May and October) when ticket demand and crowds are at their absolute peak.

Getting There and Entering the Forbidden City

Location and Entrances

The Forbidden City is located in central Beijing, just north of Tiananmen Square. It is a one-way attraction: all visitors enter through the south gate (Meridian Gate) and exit from the north gate (Gate of Divine Prowess) or, optionally, the east side gate. Keep this in mind when planning your route – you’ll be walking northward the entire time. Once you exit, you cannot re-enter without a new ticket. The main entrance, Meridian Gate (Wǔmén), is the iconic U-shaped gate with five arches, topped by towers – this is where you’ll start your tour.

Metro: The easiest way to reach the Forbidden City is by Beijing Metro. Take Line 1 to Tian’anmen East (天安门东) or Tian’anmen West (天安门西) station – both are about a 5-10 minute walk to the entrance. From either station, follow signs to Tiananmen Square/Tiananmen Tower and then walk north toward the large red gate with Mao’s portrait (that’s Tiananmen Gate, the entrance to the outer courtyard). Pass through the security checkpoint under Tiananmen Gate, cross the big plaza beyond it, and you’ll reach Meridian Gate just ahead. You can also take Line 2 to Qianmen Station and walk north through Tiananmen Square, but that’s a longer walk; Line 1 is more direct.

Tip: If you plan to visit Tiananmen Square first, Line 2 to Qianmen is a good choice. Otherwise, stick with Line 1.

Bus: Numerous public buses stop near Tiananmen Square as well (routes 1, 2, 52, 82, etc. to Tiananmen East/West). Beijing’s buses are cheap and reliable, but can be tricky for non-Chinese speakers. If you’re comfortable, they do stop very close to the entrance.

Taxi / Rideshare: If taking a taxi or rideshare (e.g. Didi), note that direct drop-off at the Meridian Gate is not possible. The area in front of the Forbidden City is pedestrianized and heavily secured, so vehicles will have to let you off a few blocks away. The taxi can approach from the east along Chang’an Avenue or from the west; a common drop-off point is near the National Museum or Zhongshan Park, from which you’ll walk a few minutes to the entrance. Be sure to carry the name and address in Chinese (故宫博物院南门 – Palace Museum South Gate) to show the driver. Traffic in central Beijing can be heavy, so consider the subway if timing is tight.

Security Checks and Entry

Arrive early for security. Before reaching Meridian Gate, all visitors must go through a security screening (including bag x-ray and metal detector) either at the outer perimeter or just before the gate. If coming via Tiananmen Square, you’ll clear one security check to enter the square and another at the palace entrance. Lines can form, especially on weekends, so factor in an extra 10-20 minutes. Large bags may not be allowed in (and you wouldn’t want to lug them around anyway).

At the Meridian Gate entrance, you’ll see clearly marked lines for entry. Have your passport and reservation QR code (if you have one) ready. They will scan your passport, which pulls up your ticket in the system. Once it verifies, you’re good to go inside. From this point, you’re standing in the outer courtyard of the Forbidden City!

Tip: There is a free left-luggage service for big bags at the entrance. New rules from 2023 ban large suitcases and wheeled luggage from being brought inside the Forbidden City. If you’re in transit (for example, straight from a flight or train with your bags), you can deposit luggage at the Visitors’ Service Center just inside Meridian Gate, and the staff will transfer your bags to the north exit for you to pick up when you finish. This convenient service saves you from backtracking all the way to the south gate for your bags later. There’s no fee (just a refundable deposit). Otherwise, bring only a small backpack or day bag and wear comfortable walking shoes – you’ll be covering a lot of ground on foot!

Rules and Etiquette for Visitors

The Palace Museum is a treasure of China’s heritage, and there are some important rules in place to protect the site and ensure an enjoyable visit for everyone:

- No large bags or wheeled items: As mentioned, suitcases, large backpacks, folding bicycles, scooters, and roller bags are not allowed inside. Security will turn these away at the entrance. Stick to a small daypack. (Wheelchairs and strollers for young children are exceptions and are permitted).

- Real-name entry: Each ticket is tied to an individual’s ID. You cannot purchase multiple tickets under one name – if you’re visiting as a group, ensure each person (especially foreign visitors) has their own passport with a ticket reserved. Remember your passport on the day – no ID, no entry.

- Prohibited items: Weapons or sharp objects, obviously, but also avoid carrying any objects that could damage relics (e.g., ink, paint). Beijing’s sites also ban drones, so leave the drone at home – flying one over the Forbidden City is strictly forbidden for security reasons. Selfie sticks are technically allowed, but please use them with caution in crowded areas (and some indoor exhibits might ask you not to use them).

- Photography: Personal photography is generally allowed outdoors and in most areas – feel free to snap away at the beautiful architecture! However, flash photography is prohibited in indoor exhibition halls and around delicate artifacts (signs will remind you). Tripods and professional video rigs are not allowed without prior permission. Recently, the museum has also cracked down on commercial photoshoots – you might see people dressed in Qing dynasty costumes taking pictures, but any bulky gear like reflectors or rolling cases is banned to protect the grounds. If you want to dress up in imperial attire for fun, that’s okay, just be respectful and don’t block others. Also, no livestreaming inside indoor galleries per new regulations.

- No touching or climbing: This seems obvious, but with so many beautiful carvings and ancient artifacts, it’s worth a reminder: do not touch paintings, antiques, or the old structures. Oils from fingers can damage centuries-old surfaces. And though those marble thrones and railings might look tempting to climb onto for a photo, it’s not allowed – security personnel will whistle at anyone who crosses barriers or ropes. Stay on the visitor paths and don’t enter cordoned-off areas.

- No smoking or open flames: The Forbidden City is a wooden complex – fire is a huge threat. Smoking is prohibited everywhere inside (as it is at virtually all Chinese tourist sites). You’ll also find fire extinguishing tanks (big bronze cauldrons) placed throughout the palace – these were the water barrels used in imperial times to combat fires. They’re a historic feature, but also a reminder of fire safety.

- Food and drink: Officially, outside food and drinks are not permitted inside the Forbidden City. Large snacks or picnic lunches will likely be stopped at the bag check. The rule is to protect the relics and keep the environment clean. That said, bringing a water bottle is fine and even advisable – just no eating a meal inside the palace. There are some cafés and snack shops within the complex where you can buy water or a quick bite (see Facilities below). If you do carry a small snack (for example, for young kids), be discreet and always carry out your trash.

- Respect the space: This is a place of great cultural importance. Avoid loud behavior or any actions that would show disrespect (for instance, don’t shout or play music in the sacred halls). Dress comfortably but consider covering up a bit out of respect – while there’s no strict dress code, extremely revealing clothing might be seen as inappropriate in this historic environment. Above all, move with care and mindfulness – the palace has stood for centuries, and we are guests in its halls.

- Stay on the route: Visitors must generally follow a one-way route from south to north. Don’t attempt to go backwards against the flow, and note that re-entry is not allowed if you exit from the North gate mid-visit. Plan to see everything you want before you leave the grounds. If you exit at the north and realize you missed something, unfortunately, you can’t turn around – you’d have to buy another ticket for another day.

Guided Tours and Audio Guides

As you wander through courtyards and throne rooms, you’ll probably want some background on what you’re seeing – the Forbidden City is rich with stories and symbolism. There are a few ways to enrich your visit:

- Audio Guides: The Palace Museum offers an excellent audio guide device that you can rent at the entrance. These cost about ¥40 and are available in over 30 languages (English, French, Spanish, Japanese, Korean, etc.). The Chinese versions (Mandarin, Cantonese, Hakka dialects) are only ¥20. The device is easy to use – you punch in the number of the exhibit or area you’re at, and it narrates the history and significance. The audio guide allows you to explore at your own pace but still get detailed explanations of key sights. Tip: There is a refundable deposit (often around ¥100 or a valid ID) required to rent the audio guide – confirm the current deposit policy on site. And bring your headphones if you prefer (though a single-ear earpiece is usually provided).

- Free App/QR Codes: As of 2025, the Palace Museum has a mobile app and some QR codes on-site that provide information in English and Chinese. If you have mobile data or connect to the museum’s Wi-Fi, you can try scanning QR codes near some exhibits for details. However, the coverage can be spotty, and using your phone constantly might distract from the experience.

- Guided Tours (in-person): Hiring a human guide can bring the Forbidden City’s history to life. There are usually official tour guides available at Meridian Gate, who can be hired on the spot. Rates can vary (often negotiable) but expect around ¥200–¥300 for a private English-language tour of 2 hours (price per group, not per person). A guide will navigate you through the key sites, share fascinating stories (like the antics of Emperor Qianlong or Empress Dowager Cixi’s life in the palace), and answer questions. This can be great if you prefer a personal touch or have lots of questions. Ensure any guide you hire is licensed – official guides should have a badge.

- Pre-booked Tours: Many travel agencies offer Forbidden City tours, from half-day small group tours to full private tours that include hotel pickup. Some “VIP” tours bundle in extras like a guided walk through less-visited sections, or combined itineraries that include Tiananmen Square and Jingshan Park. If you’re interested in Chinese history, a knowledgeable guide can greatly enhance your understanding, but if you prefer to wander freely, the audio guide or a good guidebook might suffice.

- Do You Need a Guide? It depends on your interest level. Casual visitors can enjoy the spectacle of the architecture and read the on-site signage (which is bilingual Chinese/English) for context. Major halls have plaques explaining their use. But the Forbidden City is brimming with hidden details and stories – having some guidance (audio or human) will reveal things you might otherwise miss. If you’re the type who loves historical anecdotes or wants to know why things are the way they are (e.g., the significance of the number of dragon carvings, or the daily routine of the emperor), consider a guide. If you just want to take in the ambiance and grandeur, you can certainly self-tour successfully.

(Note: Beware of unlicensed “guides” lingering outside the Forbidden City who offer cheap tours – some are scammers or will pressure you into buying souvenirs. It’s safer to use the official channels inside or book through a reputable tour company.)

Facilities and Amenities Inside the Forbidden City

While touring the vast palace, it’s good to know what amenities are available to visitors. Here’s what to expect inside:

- Restrooms: There are several restrooms strategically located throughout the Forbidden City, and they’ve been improved significantly in recent years. You’ll find Western-style toilets and accessible stalls at main restroom areas near the entrance (Meridian Gate), around the middle (by the Hall of Preserving Harmony), and at the north exit. Additional toilets are scattered in each major area (just look for the WC signs or ask staff “Cèsuǒ zai nǎ? 厕所在哪?”). It’s wise to carry some tissues or toilet paper, as some restrooms might not stock it (though major ones usually do). Also, most toilets have hand sanitizer, but bringing a small bottle is a good idea. The facilities are generally clean by tourist attraction standards, thanks to regular maintenance.

- Drinking Water: Especially in summer, stay hydrated. It’s fine to bring your own water bottle (security won’t confiscate sealed drinks or empty bottles). There are a few water vending machines and kiosks inside selling bottled water and soft drinks (expect a markup – maybe ¥5-10 for a bottle). A couple of the souvenir shops also sell drinks. Hot water: Chinese attractions sometimes have hot water dispensers (for tea or infants), but it’s less common here – don’t count on it. Just bring enough water or be ready to buy.

- Eating: As noted, outside food is officially not allowed, but you won’t starve inside. There are a handful of eateries:

- The Palace Museum Restaurant (故宫餐厅) – a casual cafeteria-style restaurant near the Hall of Ancestry Worship (which houses the Clock Gallery). It serves simple Chinese set meals, snacks, and drinks. Expect things like noodles, fried rice, steamed buns, and maybe hot dogs or chicken wings. It’s not gourmet, but on a cold day a hot bowl of something here can be a lifesaver. Prices are reasonable (around ¥40–¥50 for a basic set meal, which is inexpensive for inside a major attraction). There’s indoor seating and some outdoor tables. It does get busy at lunchtime (around 12–1 PM), so if you want to eat here, try to come either slightly early or later to avoid the queues.

- The Imperial Icehouse Restaurant (冰窖餐厅) – tucked in the west side of the Forbidden City near the Cining Palace (Palace of Compassion and Tranquility). This is a unique spot: it’s set in an actual 18th-century ice cellar that was used by the imperial household to store ice during summer. Now it’s converted into a small café/restaurant. The ice cellar is semi-underground with thick walls – stepping inside, you’ll notice it’s cooler, a neat escape in summer. They have a cafe area selling coffee/tea and light snacks, and a dining area with a menu of simple Chinese dishes. The ambience is very special – old vaulted brick ceilings and “ice” decor – giving you a literal taste of history. Drinks are ~¥30 and snacks ~¥18, according to one report. The Icehouse restaurant is open Tuesday to Sunday, roughly 10 AM to 4 PM (no service on Mondays, in line with the museum closure). If you find it, it’s worth a stop for the experience alone.

- Snack Stalls: There are a couple of small snack kiosks in the courtyard areas (one near the Imperial Garden toward the north, and sometimes one in the central courtyard). They sell items like ice cream (the Palace Museum’s imperial-themed ice creams, shaped like dragon or carp are a hit on social media), packaged snacks, and drinks. Prices are a bit high but not outrageous for a tourist site.

- Afternoon Tea (Wanchun Pavilion): In the Palace of Earthly Tranquility (Kunning Palace) area, there has been an “afternoon tea” setup called Wanchun Jinfu Afternoon Tea. It offers a set menu of imperial-style snacks and teas in a quaint courtyard atmosphere, with decor that makes you feel like a palace lady or lord. Drinks ~¥30, snacks ~¥18. This is more of a niche experience and may not always be open, but keep an eye out if exploring the inner court near Kunming Palace. Generally, eating options are limited inside, so don’t come expecting a full range of restaurants. If you just need a quick bite or drink to refuel, you’ll be covered. If you want a larger meal, plan to eat after your visit (see the Nearby Restaurants section below for ideas).

- Souvenirs and Shops: The Forbidden City has a gift shop empire! There are multiple gift shops and stands, especially near the major halls and the exits. The main Palace Museum Gift Shop is near the Gate of Divine Prowess (north exit) – a large store selling everything from postcards and books to silk scarves, jewelry, porcelain replicas, and the wildly popular Palace Museum-branded merchandise. In recent years, the Palace Museum has become famous for its creative cultural souvenirs, from miniature building models to even palace-themed makeup like lipsticks and perfumes. These make for fun and unique gifts. Prices range from cheap trinkets to high-end artisan items. An interesting fact: the museum reportedly earns over ¥1.5 billion a year from cultural product sales – so you know they have good stuff! Take some time to browse; even the shopping experience reflects Chinese art and design. Smaller kiosks throughout the complex sell things like guidebooks, maps, and small souvenirs (fans, keychains, etc.). Tip: If you plan to buy souvenirs, carry cash. Some big shops may accept credit cards, but many smaller ones or pop-up stands might be cash or Chinese mobile payment only.

- Benches/Seating: The Forbidden City involves a lot of walking on stone pavements. There are some benches and resting areas, particularly near the garden at the north end and alongside walkways. Don’t hesitate to take a rest if you need – maybe under the shade of an ancient cypress tree in the Imperial Garden. Just avoid sitting on restricted areas or steps of halls.

- Accessibility: The palace has made strides in improving accessibility. Many main routes have wheelchair ramps over the high thresholds, and there are designated accessible pathways for wheelchair users. Some buildings even have elevators or lifts to get up to platform levels (for example, the main throne hall area has a lift for those who can’t climb the steps). Free wheelchairs can be borrowed from the visitor center at the entrance (Meridian Gate) with a ¥500 refundable deposit. You can use it for a one-way trip and return it at the north exit when done. If you have mobility issues or elderly family members, this service can be incredibly helpful (even if you don’t need a wheelchair full-time, using one to cover the long distances can save energy). Keep in mind, some more narrow or ancient sections (like steep stairs to towers, or cobbled lanes) might not be accessible, but you can still see all the primary areas. The crowds can be a challenge for those with limited mobility, so try to visit at off-peak times for an easier experience.

- Visitor Center Services: Just inside the Meridian Gate, the Visitor Service Center provides various services – from the aforementioned luggage storage and wheelchair loans to lost & found, first aid, and sometimes English-language information brochures. If you need help or have questions, this is a good place to inquire. Staff and signage in English are available.

- Wi-Fi: There is reportedly free Wi-Fi within the Forbidden City for visitors, though the connectivity may not be great in all areas. Look for “Palace Museum WiFi” or similar. Don’t rely on it for anything crucial.

- Rest and refresh: Visiting in summer? Pack a portable fan or cooling towel; you’ll thank yourself. In winter, pocket warmers can be nice. And year-round, Beijing’s air can be dry and occasionally smoggy – having a light mask or scarf is helpful if the air quality is poor on the day of your visit (check the AQI index; if it’s very high, consider rescheduling your outdoor activities).

By being prepared and knowing what’s available inside, you can focus on enjoying the imperial wonders without worry. Now, let’s dive into those wonders – here are the must-see highlights inside the Forbidden City that you shouldn’t miss.

Must-See Highlights Inside the Forbidden City

Entering through Meridian Gate, you’ll traverse the same route emperors did, from the grand outer court to the intimate inner court. The Forbidden City is huge (over 9,000 rooms!), but certain sites stand out as essential stops. Here are the top highlights to look out for:

- The Three Great Halls (Outer Court): These are the three massive ceremonial halls on a triple-tier marble terrace at the heart of the Outer Court. They embody the power of the emperors:

- Hall of Supreme Harmony (太和殿 Tài Hé Diàn): The largest and most important hall, this was the throne room where the Emperor held court and major ceremonies. Inside sits the magnificent Dragon Throne – peek through the doorway to see the gilded throne and ornate ceiling with a coiled dragon. This hall, rising above the courtyard on its marble platform, was where emperors’ coronations, imperial weddings, and New Year celebrations took place. It’s the iconic image of the Forbidden City.

- Hall of Central Harmony (中和殿 Zhōng Hé Diàn): A smaller square hall just behind the Supreme Harmony hall. It was a preparation room – the emperor would stop here to rest and mentally prepare before ceremonies. Think of it as the royal green room.

- Hall of Preserving Harmony (保和殿 Bǎo Hé Diàn): The last hall in this trio, used for banquets and later for the final stage of the imperial civil service examinations. Aspiring officials once took the grueling exams right in this hall. Today it often houses large exhibits. The massive ramp behind it (with carved dragons) is an art piece itself, used to haul the throne up into the hall.

Why they’re special: These three halls sit atop a vast courtyard and offer a jaw-dropping vista of imperial architecture. They are usually crowded, but be patient and step up to each doorway to glimpse the interiors. The scale and symbolism (like the number of roof figurines – 10 on the Supreme Harmony Hall, indicating supreme status) are fascinating details a guide or audio guide can explain. - Meridian Gate and Golden Water Bridges: Right after you enter, you’ll cross the Golden Water River via ornate stone bridges. Pause here for a great photo looking toward the Three Great Halls. Meridian Gate itself (behind you) is impressive – note it has five arches; only the emperor could use the central arch in imperial times!

- The Inner Court & Palace of Heavenly Purity (乾清宫 Qiánqīng Gōng): Passing through the Gate of Heavenly Purity, you enter the Inner Court – the private living quarters of the emperor and family. The first building here is the Palace of Heavenly Purity, the emperor’s main residence (especially in the early Qing era). It’s a large hall where emperors also held morning meetings in their pajamas (more or less) to avoid trekking to the outer court. Look inside to see the throne and living area setup. Fun fact: later Qing emperors chose to live in the cozier Hall of Mental Cultivation (养心殿 Yǎngxīn Diàn) just west of here – you can peek into that side hall too if it’s open, to see where Emperor Puyi last lived before eviction.

- Palace of Earthly Tranquility (坤宁宫 Kūnníng Gōng): At the north end of the Inner Court’s central axis, this was the Empress’s residence. It flanks the Inner Court along with Heavenly Purity Palace, and between them sits the small Hall of Union (where the imperial seals were stored). The Palace of Earthly Tranquility was later used as the bridal chamber for imperial weddings – inside, you can see red “double happiness” decorations from when an emperor married here.

- Imperial Garden (御花园 Yùhuāyuán): At the very north end, before you exit, don’t miss the beautiful Imperial Garden. This classic Chinese garden is compact but packed with pavilions, rockeries, gnarly ancient trees, and sculpted pathways. Check out the two cypress trees entwined together – nicknamed the “Love Tree,” symbolizing marital fidelity (legend says they were planted during the Ming dynasty and grew together). The garden’s four corner pavilions represent the four seasons. It’s a lovely place to rest and reflect at the end of your tour, often with musicians playing classical instruments in the background. (Note: It can also be crowded as everyone funnels through here to exit, but the scenery is worth it.)

- Treasure Gallery (Palace of Tranquil Longevity, 宁寿宫 Níngshòu Gōng): Tucked in the northeast section of the Forbidden City is a complex built by Emperor Qianlong for his retirement, called the Tranquil Longevity Palace. Though Qianlong never actually retired there, today it houses the Treasure Gallery, a separate exhibition of imperial treasures. If you bought the extra ticket, you can enter this area (it’s adjacent to the Imperial Garden). Here you’ll see astonishing jewels, gold and jade artifacts, imperial robes, and ceremonial items up close. Even if you skip the gallery, at least go up to the entrance to see the famous Nine-Dragon Screen just outside – a 20-meter-long glazed wall with nine vividly colored dragons, one of only three such screens in China. It’s a great photo spot.

- Clock and Watch Gallery: On the east side (in the Hall for Ancestry Worship), this exhibit requires the other ¥10 ticket. It displays about 200 antique clocks and watches, many gifts from foreign envoys or made by Chinese craftsmen for the emperors. Some are incredibly elaborate – gilded clocks with moving birds, automatons, etc. There are scheduled demonstrations when some of the clocks are wound up and put into action (usually a few times a day). If timing and interest align, it’s a charming stop to see the ingenuity of timepieces from a bygone era.

- Six Western Palaces & Six Eastern Palaces: These are clusters of smaller residence halls on the west and east sides of the Inner Court. They were the living quarters of imperial consorts and children. Many are now galleries (showcasing paintings, ceramics, etc.). One noteworthy palace in the west is the Palace of Eternal Spring and Palace of Gathered Elegance (储秀宫 Chǔxiù Gōng) – known as the residence of Empress Dowager Cixi when she was a young concubine. Cixi gave birth to a future emperor (the Tongzhi Emperor) in the Palace of Gathered Elegance. On the east, the Hall of Literary Glory often has special exhibitions, and the Palace of Abstinence (where emperors fasted before ceremonies) can be an interesting quick look. While not everyone ventures into these side palaces, if you have time, wandering through a few will give you a more intimate sense of court life (and they’re blissfully less crowded).

- Belvedere of Pleasant Sounds (畅音阁 Chàngyīn Gé): This is an ornate three-story wooden opera house located in the Tranquil Longevity Palace garden (north-east area). Emperors and empresses watched Peking Opera performances here. It has an impressive stage design with trapdoors connecting levels. If open, you can peek inside to see the stage. It’s a treat for architecture and opera buffs alike.

- The Corner Towers: Though not inside the main tour route, the four corner towers of the Forbidden City’s walls are iconic (you may have seen them in photographs). They are intricately built with 72 ridges – a marvel of old Chinese carpentry. You can’t climb them, but as you leave from the north gate, glance to the northwest or northeast to appreciate these towers perched on each corner of the wall. They’re especially photogenic from the outside, across the moat.

Every hall and courtyard has its story, but the above spots are some highlights you’ll want to be sure to catch. As you explore, also notice the small details: the Imperial red walls and golden roof tiles, the guardian lion statues (male lion with a ball, female with a cub), the sun-dial and grain measures in front of the Hall of Supreme Harmony (symbols of justice and authority), and the pavement stones (some still bear wear from centuries of foot traffic). The Forbidden City rewards those who take the time to look closely. Feel free to venture down less-traveled paths – you might find a quiet courtyard to imagine palace life away from the crowds.

Top Nearby Attractions and Food Spots

One of the great things about the Forbidden City’s location is that it’s surrounded by other noteworthy sights and fun places to visit. After (or before) your palace tour, you can easily explore a bit more of Beijing’s cultural and culinary scene. Here are some top attractions nearby, plus local restaurants and cafés to consider:

Cultural & Historical Attractions Near the Forbidden City

- Tiananmen Square (天安门广场) – Directly south of the Forbidden City. This is the immense public square that famously lies just beyond the Forbidden City’s front gate. It’s worth a stroll to see:

- Tiananmen Gate & Square Monuments: The Gate of Heavenly Peace (Tian’anmen) with Chairman Mao’s portrait is where you likely passed through en route to the palace. In the square itself, see the Monument to the People’s Heroes (the obelisk in the center) and the Great Hall of the People (China’s parliament building on the west side).

- Mausoleum of Mao Zedong: On the south side of the square, you can (if interested) visit the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall, where Mao’s embalmed body is on display. It’s open mornings with free entry (passport needed). Expect lines and a brief, solemn viewing.

- National Museum of China: On the east side of the square, this huge museum is one of the largest in the world, covering all periods of Chinese history. If you still have museum energy after the Palace Museum, it’s definitely worth visiting (free entry with ID, closed Mondays). You can easily spend 1-2 hours seeing everything from ancient bronze vessels to modern art.

- Practical: Tiananmen Square is open and free to walk; it has strict security checks (separate from the Forbidden City’s). At sunrise and sunset, you can witness the daily flag-raising and lowering ceremony by People’s Liberation Army guards – a very popular brief ceremony.

- Jingshan Park (景山公园) – Immediately north of the Forbidden City, across the street from the north exit. This is a must-do after exiting the Forbidden City. Jingshan is an artificial hill (created from the earth excavated to build the palace moat) with a charming park. A short hike up to the Wanchun Pavilion at the summit provides a stunning panoramic view of the entire Forbidden City spread out below. It’s the best vantage point for photography – you’ll see the golden rooftops in all their glory, and the Beijing skyline beyond. The park itself is lovely, with flower gardens and locals often practicing tai chi or singing folk songs. Entrance fee: just ~¥2-¥5. It’s open early until late (you could even catch a sunset over the Forbidden City from here). Tip: The climb is not too hard – about 10-15 minutes of stairs/path – and absolutely worth the reward at the top. Don’t forget to turn around northward too; you get views of Beijing’s Drum and Bell Towers from the hill on a clear day.

- Beihai Park (北海公园) – About 10 10-minute walk west from the Forbidden City’s north gate (or a quick taxi). This large historic park features a scenic lake (Beihai) with paddle boats and the famous White Dagoba (a white stupa) on an island. Beihai Park was once an imperial garden as well, linked to the Forbidden City, and it’s full of charming temples, pavilions, and walking paths. It’s a great place to relax after the intensity of the Palace Museum. You can rent a rowboat or just stroll. Entry is ~¥10. Highlights include the Nine-Dragon Screen (yes, another one – different from the Forbidden City’s, with seven-color glaze) and the Circular City with a huge jade jar. If you have half a day free, combining Jingshan Park and Beihai Park makes for a pleasant outdoorsy extension of your Forbidden City visit.

- Zhongshan Park (中山公园) – Immediately west of the Forbidden City’s south gate. This is a smaller park adjacent to Tiananmen. It’s the former Altar of the Gods of Land and Grain, now a tranquil park with pavilions and peonies. Named after Sun Yat-sen (Sun Zhongshan), it’s a quiet spot to catch your breath in the shade. There’s a small entry fee (~¥3). Not a must-see, but if you have extra time and want a peaceful stroll, you could pop in here either before entering the Forbidden City (to kill time if you’re early) or afterwards.

- Wangfujing Street (王府井) – About 1 km east of Tiananmen (reachable by a short taxi ride or a couple of metro stops to “Wangfujing” on Line 1). This is Beijing’s famous pedestrian shopping street. If you’re looking to do some shopping or try some street snacks after your cultural tour, Wangfujing is the spot. The main street has modern malls, bookstores, souvenir shops, and the well-known Wangfujing Snack Street (a side alley where you can sample things like candied fruits, fried insects – if you dare – and other Beijing snacks). It’s a lively place in the evenings. You’ll also find the Beijing Foreign Language Bookstore and plenty of places to buy tea, silk, etc. It’s a change of pace from the historical sites and gives you a taste of modern Beijing commerce.

- Hutongs and Shichahai (什刹海) area – A bit further north-west (about 2 km from the Forbidden City). If you want to delve into Beijing’s old alleyway neighborhoods, head to the hutongs around Houhai Lake (Shichahai). A short taxi ride (~10 minutes) can take you to the Nanluoguxiang (南锣鼓巷) hutong, which is a trendy renovated alley full of boutiques, cafés, and bars. Or visit Prince Gong’s Mansion (恭王府), a preserved Qing Dynasty prince’s residence with beautiful gardens. In the evening, the Houhai lakeside area comes alive with quirky bars and live music. This can be a nice way to unwind after a day of sightseeing – it’s still historical (some hutong courtyard houses here are centuries old) but with a fun nightlife vibe.

- National Centre for the Performing Arts (国家大剧院) – About a 15-minute walk west from Tiananmen Square. Also nicknamed “The Egg” for its futuristic oval shape, this modern opera house/theater is a fascinating contrast to the Forbidden City’s ancient architecture. If you’re an architecture buff, it’s worth walking by or even taking a tour inside. Occasionally, there are evening performances (symphony, opera, ballet); attending one is a memorable experience. If not, at least see the building’s exterior reflected in its surrounding pool.

In summary, you’re in a rich historical corridor of Beijing. A popular itinerary is: morning at Tiananmen Square, then Forbidden City late morning to afternoon, then Jingshan Park for sunset, and finally roast duck dinner nearby (see below!). Or do Forbidden City in the morning, lunch, then explore Beihai Park or Wangfujing in the afternoon. Mix and match as time allows.

Restaurants & Cafés Nearby

After walking the imperial grounds, you’ll likely have worked up an appetite. Fortunately, the area around the Forbidden City offers some great dining options, including the famous Peking Duck. Here are a few recommendations for nearby eats and drinks:

- Siji Minfu Roast Duck (四季民福烤鸭店, Gùgōng branch): Location: Just outside the Forbidden City’s east wall (a short walk from East Prosperity Gate or a 15-min walk from the north exit). This is one of Beijing’s most popular Peking duck restaurants, loved by locals and visitors alike for its quality and reasonable prices. The fact that it’s right by the Forbidden City (some tables even have views of the palace walls) makes it extremely popular. Here you can feast on perfectly roasted Peking duck – the capital’s signature dish – with all the fixings (pancakes, scallions, hoisin sauce). Their menu also has other classic Beijing cuisines and sides. Expect a wait during peak meal times – it’s common to take a number and maybe wait 1-2 hours in the evening (you can stroll nearby or wait in their lounge). If you go at off-peak hours (like a late lunch around 2-3 PM), you might get in faster. The duck is worth it, though – crispy skin, succulent meat, carved at your table. Prices are moderate (half a duck ~¥158). No reservations, so plan accordingly. Tip: If the wait is too long, consider getting take-away duck pancakes from their deli counter or try another branch of Siji Minfu (there’s one near Tiananmen Square as well).

- Quanjude Roast Duck (全聚德): Location: The most famous branch is on Qianmen Street (south of Tiananmen Square, about 2 km from Forbidden City). Quanjude is the century-old roast duck institution in Beijing, known worldwide. It’s a bit touristy and pricier than Siji Minfu, but it’s a piece of history – they’ve been serving roast duck since 1864. If you head down to Qianmen pedestrian street, you can dine here and also explore that area’s old Beijing charm. They too have multiple floors and sometimes wait times. Many say the duck is great but some locals now prefer Siji Minfu or other newer spots. Still, for nostalgia and tradition, Quanjude is a top pick. (If you’re not heading toward Qianmen, skip this in favor of Siji Minfu or another spot closer.)

- TRB Forbidden City (TRB 紫禁城): Location: In a hutong just east of the Forbidden City (near Donghuamen). This is a fine dining option for those who want to splurge on a special meal. TRB stands for Temple Restaurant Beijing – they have a few high-end restaurants, and this one offers western contemporary cuisine in a beautiful courtyard setting with some views of the Forbidden City walls. It’s expensive (expect a tasting menu over ¥500 per person), but the service is top-notch, and it’s often ranked among Beijing’s best restaurants. If you’re celebrating or just want to treat yourself after a long day of touring, you might consider a reservation here. (Jacket not required, but smart casual attire fits the ambiance.)

- Local Eateries in Hutongs: South of the Forbidden City, in the Dengshikou or Donghuamen areas, there are plenty of smaller restaurants and street food. If you exit from Donghuamen (East Gate), you could wander into the hutongs opposite and find dumpling shops, noodle joints, and more. For instance, the Baochao Hutong area or North Luogu Alley has cute cafes and bars. While not “next door,” they are within a short taxi ride.

- Cafés: If you just need a coffee or a break, check out the Corner Tower Café (角楼咖啡) just outside the Forbidden City’s north gate (to the west side). This cafe opened in 2018 in a restored building by the moat, and quickly became popular for its unique location. You can sip a Forbidden City-themed latte with a view of a corner watchtower. They serve coffees, teas, and pastries with palace-inspired names. Prices are like Starbucks range (¥30-40 for coffee). The interior blends modern chic with traditional elements. It’s a perfect spot to rest your legs after touring – and you’ll be literally drinking in the atmosphere of the palace. There’s also a Starbucks a bit further east along Chang’an Avenue, but when in Beijing, the Corner Tower Cafe is far more atmospheric! (Also, check our article about the best Cafes in Beijing)

- Haidilao Hot Pot: If you want a completely different food experience for dinner, and you’re not too far gone with fatigue, Haidilao (a famous Chinese hot pot chain) has a location at Wangfujing. Hot pot is fun and interactive – you cook meats and veggies in bubbling broth at your table. Haidilao is renowned for its service (manicures while you wait, aprons and hair ties provided, etc.). It’s about a 20-minute walk or a short taxi ride from the Forbidden City area. A great option, especially on a cold day.

- Snacks at Jingshan Park: Not exactly a restaurant, but if you climb Jingshan for the view, at the base or around the park, there are often vendors selling candied hawthorn skewers (tánghúlu) – a classic Beijing sweet treat – or chilled cucumber snacks. Nice for a quick taste of local flavor.

Beijing has endless food choices, but the above are convenient to the Forbidden City and offer a mix of must-try local cuisine (Peking Duck and hot pot) and relaxing cafe experiences. Remember that meal times in China tend to be earlier – lunch around 12, dinner around 6-7. If you plan to dine right after your Forbidden City visit, you might hit the tail end of lunch or need a snack to hold you until an early dinner.

Practical Tips for First-Time Visitors

Visiting the Forbidden City (and China) for the first time can be a bit daunting, but these practical tips will help your trip go smoothly:

- Language Help: While major signs and descriptions in the Forbidden City are in both Chinese and English, most staff (security, ticket checkers) speak limited English. It helps to know the Chinese name “故宫 (Gùgōng)”, which means Forbidden City, and “故宫博物院 (Gùgōng Bówùyuàn)” for the Palace Museum. If you need directions, you can show these names or say “Gùgōng” to taxi drivers. Consider carrying a guidebook or an offline translator app for deeper info or communication. That said, Beijing is used to international tourists – you’ll find basic English info and likely other travelers around who might help. Audio guides and guided tours (see above) can bridge any language gap in understanding the history. On the street, having your destination written in Chinese (e.g., your hotel, nearest subway stop) is invaluable.

- Cash and Cards: China has gone very digital with payments (Alipay, WeChat Pay are ubiquitous), but as a foreigner, you might not have those set up. Carry sufficient Chinese Yuan (cash) for tickets, small purchases, and food. The Forbidden City’s online ticket must be paid with a card (if you book through the official site, it might accept international Visa/MasterCard – if not, an agent can help). On site, larger gift shops might accept credit cards, and some places might now accept foreign mobile payments, but it’s not guaranteed. ATMs are available in Beijing, including some international bank ATMs around Wangfujing. Withdraw some yuan beforehand so you’re prepared. The Palace Museum entry itself you’ll prepay, but things like snacks, or a rickshaw ride in a hutong, etc., will need cash. Exchange rate: As of 2025, roughly 1 USD ≈ 6.5–7 CNY (yuan). So that ¥60 ticket is under $10 USD – great value!

- Transportation in Beijing: The city is huge, but public transport is efficient. The subway can get you to all major attractions cheaply (3-5 yuan a ride typically). For the Forbidden City, we covered the nearest stations (Tiananmen East/West). Get a Yikatong transit card if staying a while – it works on subways and buses. Taxis are also relatively cheap – just have addresses ready in Chinese. Rideshare apps like DiDi Chuxing have an English version; you can link a credit card or use international options, making it easier to call a car. Many hotel concierges can also write down destinations in Chinese for you. Walking: You’ll actually do a fair bit of walking between sites around Tiananmen – distances can be deceivingly large due to the scale of the area (e.g., walking from one end of Tiananmen Square through the Forbidden City is a couple of kilometers). Wear comfortable shoes. Also, note that Beijing’s roads are wide – use pedestrian underpasses to cross big avenues like Chang’an Avenue safely rather than attempting the street level.

- Safety: Beijing is generally a very safe city for tourists. Violent crime is extremely rare. You can walk around most areas, even at night, with little worry. Around tourist spots, the main concern is pickpocketing in crowds – keep your belongings secure, especially in tight queues or packed buses. Use a money belt or an anti-theft bag if it makes you feel more secure, but simply keeping your backpack zipped and in front of you in dense crowds is usually fine. Don’t flash large amounts of cash. Scams: Around Tiananmen and Wangfujing, be cautious of the classic “tea house” or “art student” scam – a friendly local (often a younger person claiming to be a student) invites you to a tea ceremony or art gallery and then you get hit with a huge bill. Politely decline unexpected invitations from strangers. Also, only use official channels for tickets; don’t buy from scalpers outside. Police and CCTV are everywhere in central Beijing, which contributes to safety. If you need help, look for uniformed officers – some may know basic English or will find someone who does.

- Health & Comfort: Beijing’s air quality can fluctuate. Check the AQI on a weather app. On a day with heavy smog (AQI over 150-200), you might want to wear an N95 mask, especially if you have respiratory sensitivities. Summers are hot (carry sunscreen and maybe an umbrella for shade or sudden rain). Winters are cold (below freezing), so wear layers and proper coat, hat, gloves. Stay hydrated (bottled water is easily found). Public toilets in the city (outside the Forbidden City) can sometimes be squat-style – inside the Forbidden City, you’ll find some Western toilets as mentioned. It’s a good idea to carry tissues and hand sanitizer wherever you go in China.

- Transportation to Next Sites: When you’re done at the Forbidden City, it might be hard to find a taxi right at the north exit because of traffic restrictions. If you want a taxi, you may need to walk a block or two east or west. Using a ride app is handy here. Alternatively, from the north exit you can hop on a bus: Bus lines 58, 101, 103, etc., run along the north gate road and can take you toward central areas (though you need to know where you’re going). The subway isn’t right at the north exit – the closest is a bit of a walk (Line 8 “Shichahai” or Line 5 “Dongsi” are about 1.5 km away). Honestly, walking to Jingshan Park or Beihai Park is easiest since they’re right there, and from those parks, you can access other transport. Plan your next move before you exit if possible (there’s no re-entry).

- Time management: The Forbidden City is not a place to rush. Try not to cram another big attraction on the same morning or afternoon. Give yourself flexibility – if you find you’re really into it, you might spend 4-5 hours inside. If you’re quicker, you’ll still likely need 2 hours minimum. Keep an eye on the time so you don’t miss things like the Treasure Gallery if you bought that ticket (it’s toward the end of the route). There are maps available at the entrance – grab one (or use a map app). The layout is basically a grid, but it can be a little maze-like in the side sections.

- Documents: Always carry a copy of your passport (or the actual passport) while in China. You’ll need it for ticket checks, possibly for entering Tiananmen Square (real-name reservations have been implemented there as well), and it’s generally required for things like checking into hotels. It’s also a good form of ID to have on you for any random situation.

- Enjoy the moment: Finally, remember to pause and soak in the atmosphere. It’s easy to get caught up in seeing everything and taking photos of each hall. But also stand in one of those vast courtyards for a minute, imagine it centuries ago filled with officials in silk robes, or listen to the echoes of footsteps on the ancient bricks. Despite the crowds, you can find your own connection to this remarkable place.

Visiting the Forbidden City is often a highlight of any trip to China. With this guide, you’re well-prepared to navigate the practicalities and fully appreciate the wonder of this palace museum. Enjoy your imperial adventure in Beijing, and don’t forget to say zàijiàn (goodbye) to the emperors’ home as you leave – you’ll carry a bit of its history with you!

Safe travels and happy exploring!